Middle Paleolithic Era and the Emergence of Homo Sapiens

- Type of Paper: Essay

- Topic: Neanderthals, Humans, Human, Cave, Stone, Genetics, Population, Language

- Pages: 35

- Words: 9625

- Published: 2018/10/26

Check out this 30-page chapter of a sample research paper on human prehistory in the middle Paleolithic age and behold the mastery of our writers! With their assignment, homework, research, dissertation or essay help online, there is no task too hard for you to accomplish on the highest level of quality. Whenever you feel lost and uninspired or simply lack time, call out for our assistance and tackle all your academic challenges!

Middle Paleolithic

This article is divided into parts:

- Part I: General context of human life in the Paleolithic

- Part II: The Lower Paleolithic

- Part III: The Middle Paleolithic (this part)

- Part IV: The Upper Paleolithic

The middle paleolithic is the period between about 300,000 years ago until about 30,000 years ago. This period is sometimes called the Middle Stone Age in in Africa. There are large dating differences between Europe, Africa and Asia. This period overlaps the lower paleolithic (which extends past it to as late as 100,000 years ago in some places), as well as the upper paleolithic (which started as early as 50,000 years ago in some places).

For much of the middle paleolithic, Neanderthals lived in Europe and the middle east. However, the middle paleolithic also marks the emergence of modern man, our own species Homo sapiens. Genetic studies converge on dates within the middle paleolithic for both Mitochondrial Eve (170,000 - 150,000 years ago) and Y-chromosomal Adam (90,000 - 60,000 years ago). Modern humans first left Africa around 100,000 years ago, according to the Recent Out of Africa model.

Although there is some highly controversial "evidence" of art-like work from the Acheulian (Venus of Tan-Tan, Venus of Berekhat-Ram, bone artifacts from Bilzingsleben), it is not widely accepted. The earliest accepted evidence of behavioral modernity come from the middle paleolithic, which includes:

- The earliest unambiguous intentional human burials, known from sites in Croatia (130,000 years old) and Palestine (100,000 years old).

- Beads and other objects used for adornment, as well as ritual objects are known from Blombos Cave in South Africa, which date to about 75,000 years ago.

- There is evidence of long distance trade in commodities such as ochre, which may have been used for ritual purposes.

For much of the middle paleolithic humans (both modern and Neanderthals) lived in small bands, in a hunter/gatherer lifestyle. Coastal communities also included a good deal of fishing. Stone tool technology was improved compared to Acheulian techniques, as will be described later. The use of fire became widespread during this period, and humans started to cook their food.

There is significant evidence of cannibalism from this period from many different sites, in the form of bones which show marks of stone tools. However, it is not possible to be certain that such signs definitely indicate cannibalism, because they do not rule out post-mortem ritual stripping of the flesh, as has been practiced even in modern societies.

Neanderthals and the Mousterian Culture

Homo Neanderthalis is a relatively recent species of man, who became extinct as recently as 30,000 years ago. There is some controversy to their exact status, with some people believing them to be a subspecies of modern man, and others preferring to place them in their own separate species. Like Homo Sapiens, Neanderthal man also descended from Homo heidelbergensis, who probably first appeared in Africa about 600,000 years ago. Neanderthal-like traits started appearing in European Homo heidelbergensis very early, probably within the first 50,000 years (550,000 years ago). The earliest evidence of a clearly Neanderthal type of human comes from Sima de los Huesos in Spain, and has been dated to 350,000 years ago. These traits reached a peak in Europe (to represent what is currently understood as classically Neanderthal by around 130,000 years ago. Neanderthal traits were wiped out in Asia about 50,000 years ago, and in Europe about 30,000 years ago.

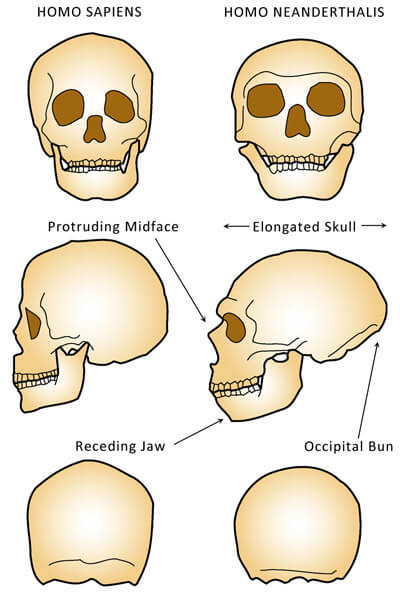

Neanderthals were about the same as modern man in average height (5' 6" for males, 5' 1" for females), but very powerfully built. Their brain size was also about the same as that of modern man (some early studies claimed it was larger, but more recent studies show that it was about the same, or slightly smaller). They were primarily hunters, and lived off large game that was common in Europe and Asia at the time. Isotopic analysis and examination of their teeth show that they were primarily carnivorous. Their skull differed markedly from modern humans in that it was more elongated antero-posteriorly, with a kind of knot at the back (occipital knot). The mid face projected slightly forward, and the chin was receding. Their bodies were very robust, with generally thicker and sturdier bones than modern humans. They had barrel shaped chests, slightly bowed legs, and wide shoulders.

Genetics

Neanderthals are the only hominids aside from modern humans where a sufficient amount of DNA has been found for sequencing. Genetic studies show some common patterns, but the interpretation is less clear. Please note that much of this information may change as the Max Planck Institute completes its project of sequencing the full Neanderthal genome.

Update

[May 6, 2010]: Scientists at the Max Planck Institute were successful in sequencing about 60% of the Neanderthal genome. Based on this work, they published a study in Science, in which they say that modern humans from Asia, Europe and New Guinea may have a small contribution from the Neanderthal genome. See the next section on Nuclear DNA for more details.

Nuclear DNA

A paper published in Science on Nov 17, 2006 by Edward Rubin states that they analyzed 65,000 base pairs of nuclear DNA of from a 38,000 year old Neanderthal femur, and found that it was 99.5% identical to modern humans. They determined that the common ancestor of humans and Neanderthals lived 706,000 years ago, and that the two species became separated 330,000 years ago. They found no evidence of interbreeding between humans and Neanderthals (though that doesn't completely rule out that it happened). They also found that the Neanderthal genome shares more similarities with the chimp genome than the human genome does, meaning that the Neanderthals were closer to chimps than we are.

Also in November 2006 an article by Richard Green and Svante Pääbo appeared in Nature, reporting the analysis of 1 million base pairs of the Neanderthal genome. They claim that the Neanderthals diverged from humans about 516,000 years ago. They found some evidence of gene flow between humans and Neanderthals, primarily from human males to Neanderthals.

On the other hand, a study by E. Pennisi that appeared in Science in May 2007 declared that there was no evidence of interbreeding between humans and Neanderthals, and pushes back the date of divergence to around 800,000 years ago.

Erik Trinkhaus, an anthropologist published a study based on fossil evidence in which he claims " To me, what happened is that the Neanderthals were [genetically] absorbed into and overwhelmed by modern humans coming into Europe from Africa, and they disappeared through this absorption". In other words, they interbred with great frequency, and the Neanderthal genome became "lost" in the human genome because of the much larger human population.

Update

[May 6, 2010]: A team led by Svante Pääbo at the Max Planck Institute in Germany published a draft of the Neanderthal genome based on DNA retrieved from 3 Neanderthal individuals (all female). About 4 billion base pairs were sequenced in total from these 3 individuals. The study provides about 60% coverage of the Neanderthal genome. They compared the Neanderthal genome to the DNA sequences of 5 modern day individuals, which included 1 person each from the San (bushmen), Yorubo (West African), French (European), Han Chinese (East Asian) and New Guinea (Australasian). Among their findings:

- Modern humans and Neanderthals diverged about 270,000 to 440,000 years ago.

- People today from Europe, Asia and Oceania are genetically closer to Neanderthals than Africans are.

- One way this can be explained is by an exchange of genes between Neanderthals and modern humans who left Africa to colonize the rest of the world about 50,000 to 80,000 years ago.

- The bulk of the gene flow appears to be from Neanderthals to modern humans, not the other way around. This may be due to the sample size and statistical methods used.

- The extent of Neanderthal ancestry in modern non-Africans appears to be about 1% to 4%. No evidence of Neanderthal genes was seen in the two native African populations, the San and the Yoruba.

- The extent of Neanderthal ancestry was equal in the French, Chinese and New Guinean individuals. This is odd, since only the European individual is from a region that was formerly inhabited by Neanderthals. It's possible that either (a) interbreeding with Neanderthals was not a prolonged process over thousands of years, but rather a brief episode that happened before modern human populations moved and split into European, Chinese and New Guinean, or (b) there was indeed more interbreeding in Europe than in Asia or New Guinea, but this has been obscured by later population movements into Europe (after the Neanderthals became extinct).

- The most parsimonious explanation for the findings is that modern humans interbred with Neanderthals soon after they left Africa, before they had split into sub-branches that colonized Europe, Asia and New Guinea.

- However, it's also possible that the Neanderthal genes go back farther in time to Africa, and belong to some subset of the African population which produced both Neanderthals and those Africans who left Africa to colonize Europe and Asia.

The study is interesting from several perspectives. First, it shows that 40,000 year old DNA can be recovered and reliably sequenced. This opens up the field for sequencing many more samples of Neanderthal and ancient modern human DNA, which should cast more light on our genetic history. Second, it shows a clear and unambiguous difference between Africans and non-Africans (those who left Africa and colonized Europe and Asia), and at the same time shows a similarity between these non-African populations. This similarity is explained either by events which happened soon after they left Africa (and hence to them but not to Africans), or else a long-standing segmentation of African populations. Further, these points of similarity between non-Africans make them genetically closer to Neanderthals than Africans are. The authors have presented what seems the most parsimonious explanation to them, which is that modern humans interbred with Neanderthals to a limited degree, soon after they left Africa, but before they split into groups that moved on to colonize Europe, Asia and New Guinea. Alternative explanations such as segmentation of populations within Africa cannot be ruled out, but seem less likely given the data.

Mitochondrial DNA

A study by Richard Green published the full mitochondrial sequence of Neanderthal DNA and concluded that Neanderthals had a much smaller population size than modern humans. This is supported by archeological findings. Once modern humans moved into areas previously occupied by Neanderthals, their archeological remains are much more common than those of Neanderthals. Other genetic studies of mt DNA also indicate that Neanderthals had a small population size and did not interbreed with humans.

The genetic verdict is therefore unresolved. All seem to agree that the Neanderthal population was comparatively small, that the divergence between humans and Neanderthals started in the middle Acheulian, probably soon after the appearance of Homo heidelbergensis, who was the likely common ancestor. The separation between Neanderthals and non-Neanderthal Homo heidelbergensis (from whom modern man is descended) was probably complete by 300,000 years ago. On the question of interbreeding, the verdict is mixed. Anthropologists, going by the fossil evidence tend to insist that interbreeding did in fact happen, mostly because there are certain well known fossils dating after the disappearance of Neanderthals that show mixed human-Neanderthal traits. The genetic evidence is more mixed, with some concluding that there is no evidence of interbreeding, and others concluding that some evidence exists.

Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology is currently sequencing a complete Neanderthal genome, and should be done by late 2009. A complete genome will give us a much better picture of the differences between Neanderthals and modern humans, and perhaps shed some light on the issue of interbreeding.

Language

It is unknown if the Neanderthals had a complex language like humans. Anatomically, they possessed most of the physiological facilitators of speech (hyoid bone, ear sensitivity similar to humans, large hypoglossal canal). Their chin was rather short, so they may have had difficulty in producing certain sounds. Genetically, they had the same version of the FOXP2 gene that modern humans have. This gene plays some role in language.

Without more evidence it's not possible to be certain of their exact linguistic status. Not many people doubt that they had some language, the question is whether it was a complex language, capable of expressing abstract thoughts, like humans do. Some people suggest that they had a sort of proto-language, that was more musical than modern language.

Mousterian Industry

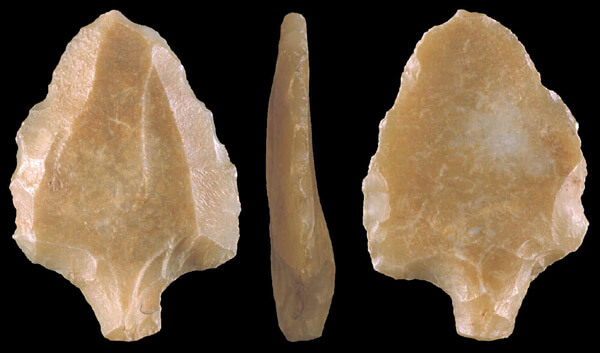

Neanderthal tools are found in great profusion at various sites across the middle east and Europe. They are often referred to as the Mousterian industry, named after Le Moustier in France, the Type site. Neanderthals used more sophisticated methods for shaping stone into tools, such as the Levallois technique (named after a suburb of Paris, France, where tools made with this method were first found), which results in much more precise control over the shape of the tool than other methods used earlier. This method was invented in the late Acheulian, but became much more common in the middle paleolithic. It produced oval shaped flakes with large triangular points, which can be used as scrapers or spear heads.

A Mousterian flake created by the Levallois Technique (left) and a Mousterian hand axe (right). Both approximately 100,000 years old.

Their toolset was fairly large, consisting of the older crusher/scrapers/pounders, as well as projectile points, serrated blades (better to saw through wood or bone), backed knives (with one end rounded off, to better fit in the hand), as well as several kinds of awls, which were probably used to make holes in hides (with implications for clothing manufacture). Neanderthals generally used soft percussors, made from bone or antler, rather than hard hammer stones. This allowed them finer control over the shaped pieces of stone. There is some evidence that Neanderthals used wood extensively, although the evidence is patchy, since wood does not preserve well.

It is unknown if Neanderthals had projectile weapons. They certainly created spears, but it appears that the spears were primarily used for thrusting at close quarters, rather than throwing. There is one case however, of a Levallois point embedded in a vertebra that indicates that the point went in on a parabolic trajectory, which may imply that the spear was thrown. We know that projectile weapons have been used since long before the Neanderthals (400,000 year old wooden projectile spears found in Schöningen in Germany), so this is not necessarily a criticism of their technology. Many modern humans (such as Maori tribesmen today) use spears primarily for thrusting, not throwing, which simply reflects a different style of hunting.

Neanderthals probably used their tools for various tasks besides hunting. Northern Neanderthals lived in a very cold environment, and surviving this could not have been easy. Obviously they used furs as clothing, probably tied to their bodies with sinew, to allow ease of movement. It seems likely that there was a clothing industry to cut hides, and arrange them together in a way to make them suitable for wearing. Microscopic residues left on tools indicate that they used their tools for wood working, which makes sense, since they probably attached their stone spear heads to wooden spears. Digging and the construction of shelters may have been another use for tools, which is mentioned in more detail below. Their tools were often made from stone not found locally, so they must have collected suitable stone from places at distances of tens of kilometers to bring to their camps.

Late Mousterian sites show a greater variety of tools and technologies. They may simply represent improvement over time, but since many of these sites are in southern locations where Homo sapiens also lived during those periods, they probably represent borrowed technology.

Neanderthal Life

Neanderthals lived in a hostile environment. After a brief interglacial around 140,000 years ago, northern Europe descended into the Würm glaciation. Surviving such a close climate poses many challenges, and all the evidence shows that Neanderthals adapted to this very well. Their relatively short, stocky bodies were well suited to conserving heat. Life in the north would not have been possible without the extensive use of fire, and Neanderthal sites show a profusion of hearths and other evidence of the regular use of fire.

There is good evidence that Neanderthals buried their dead. These burials were not as elaborate as those of Homo sapiens, but there are signs that they may have involved rituals. Burials including flowers (such as Shanidar, though the hypothesis that the flowers had ritual significance has been questioned), or other grave goods such as bison and auroch bones, ochre pigment, etc. have been found. They cared for their weak and injured, as evidenced by the survival of some people well past the years in which they would have been able to acquire food for themselves, as well as healed fractures that would have severely disabled people and led to their deaths unless cared for by others.

Neanderthals were primarily carnivorous. They acquired most of their meat through hunting rather than scavenging. Many Neanderthal sites are associated with large numbers of animal bones, and a large proportion of these bones come from adult animals in their prime, not animals who might be expected to die of natural causes and be scavenged. Traps created by Neanderthals have also been discovered, indicating that they caught large animals by trapping them, or driving them off cliff faces.

Evidence of building construction is scarcer. However, circles of mammoth bones have been found, which have been interpreted as bone huts (probably covered with skins). These are similar to bone huts created by early Homo sapiens, which are of a more recent vintage.

Sites in Turkey and Lebanon (about 43,000 - 39,000 years old), as well as later sites in France, show ochre tinted beads and other ornamental objects. It is uncertain if they reflect Neanderthal culture, since modern humans were also present in the area at the time, and they may simply be traded objects. However, even if they were traded objects, desiring a non-utilitarian object as trade goods also says something about the receiver. A bone pierced with holes that may have been used as a flute has also been found, but it's debated whether it represents a man made object.

Neanderthals were thinly populated, as shown by the relative scarcity of their sites, as well as by genetic evidence. However, at some point in time (though probably not simultaneously) they occupied a fairly large range, extending from Iraq, Iran and the levant in Asia to the southern ex-Soviet republics, and throughout Europe except the far north. Their range probably contracted and expanded in the north, as the glaciers advanced and retreated. Glaciation has no doubt destroyed many Neanderthal sites, so the true northern extent of their range is hard to pinpoint. Recently, middle paleolithic type artifacts have been found as far north as 60 °N latitude in Russia, and as far east as Siberia's Altai Mountains.

Extinction

The last Neanderthals died out about 30,000 years ago, i.e., the last Neanderthal sites showing both Neanderthal skeletal remains as well as Neanderthal artifacts, are from that age. Gorham's Cave in Gibraltar allegedly shows Mousterian artifacts dating as recently as 24,000 years ago. However, the uncertainties in dating those layers (33,000 - 23,000 years ago is the range quoted), this cannot be taken as unambiguous evidence that Neanderthals survived much past the accepted 30,000 year date. No human remains of that antiquity were found in the cave, so it's impossible to establish whether the artifacts belonged to Neanderthals or modern man, but they definitely are of the Mousterian type. A report on the BBC from 2006 claims that the cave was definitely frequented by Neanderthals as recently as 28,000 years ago.

At Abrigo do Lagar Velho, a rock shelter in Portugal, the skeleton of a 4 year old child was found, (the Lapedo Child). This skeleton has been reliably dated to 24,500 years old, and it shows an admixture of modern and Neanderthal traits. The interpretation of this skeleton is controversial, with some people saying that it definitely proves that Neanderthals interbred with modern man, and others saying it shows nothing of the sort, the child is simply deformed. Although the skeleton looks quite convincing in terms of the admixture theory, it cannot be taken as a confirmation unless more such skeletons are found. A single case may be atypical, the result of disease or genetic disorder. A larger number of similar skeletons would be more difficult to explain away.

If this theory of interbreeding is true, explaining the "extinction" of Neanderthals would be a different matter. The only thing to explain would be the extinction of the Neanderthal lifestyle, as represented by Neanderthal sites. This would simply reflect the adaptation of Neanderthals to modern man, with the newer technology replacing the old. As for the Neanderthals themselves, perhaps they didn't die out. They bred with modern humans until their traits were mixed in with the (much larger) gene pool of modern man. This also has implications about Neanderthals as a species - if they could interbreed with modern humans to produce fertile offspring, perhaps they weren't a completely different species after all. There are, of course, a lot of "ifs" in this explanation, so it cannot be accepted as fact until more evidence is forthcoming.

However, the evidence against this hypothesis is pretty strong:

- Modern humans reached as far north as the Levant 90,000 years ago. Modern human remains in Jebel Qafzeh in Israel date back to 90,000-100,000 years ago. This is an area where humans and Neanderthals coexisted - Neanderthal remains have been found in Kebara Cave in Israel dating to 60,000 years ago. There are many other places where modern humans and Neanderthals also coexisted for very long periods. If they could interbreed, why are no specimens showing mixed traits in such places? Why did modern humans and Neanderthals retain their distinct anatomically different lines through thousands of years? These arguments do not rule out interbreeding entirely, but they do show that it probably was not to any significant degree.

- Genetic studies of both nuclear and mitochondrial DNA show that humans and Neanderthals diverged about 600,000 years ago. Most of these studies show no evidence of interbreeding. All current European mt DNA lineages trace back to Africa, and are very different from mt DNA sequences found in the Neanderthal remains so far analyzed. Also, the last common patrilineal ancestor of all humans (Y chromosomal Adam) can be traced back to about 60,000 - 90,000 years ago, in Africa.

For these reasons, many people do not believe that modern humans have any significant Neanderthal admixture. Whether this is because they were unable to breed, being very different species, or because they did not choose to interbreed, for various physiological and psychological reasons, is not known. This may change, as more studies of modern human remains that predate 28,000 years (i.e., from the time of the Neanderthals) become available. Some recent studies show that modern humans in that time (> 28,000 years ago) were quite varied in their morphology, and many do indeed show Neanderthal-like traits. Also, some late Neanderthal remains, like those found at Sima de las Palomas in Spain show some modern human characteristics. So the picture may become more clouded as such discoveries are made.

Developments in Africa and the Aterian Period

Meanwhile, as these developments were taking place in Europe and the Middle East, what was happening in Africa? The middle neolithic in African is sometimes known as the "middle stone age", and begins at roughly the same period, around 300,000 years ago. Among the earliest sites showing the transition to an improved stone technology include sites in the Middle Awash valley in Ethiopia and the Olorgesailie basin in Kenya. Knives with backs (for gripping) are found as early as 300,000 years ago in Zambia.

Aterian spear head made of chert, showing the distinctive stem that was used to tie it to a spear head. From Morocco, about 45,000 years old.

Modern humans emerged in Africa between 160,000 and 200,000 years ago, according to the Recent Out of Africa theory, which is corroborated by a range of genetic evidence. A broken up cranium was found in the Omo Basin of southern Ethiopia, which looks amazingly modern, except for minor differences in the eye sockets and lower jaw. This skull has been dated to 195,000 years old. An even more modern looking skull was found at Herto, also in Ethiopia, but a bit farther north. This skull is 160,000 years old. So it seems likely that modern humans evolved in Africa some time during this period.

So who was living in Africa at the time? Who did Homo sapiens evolve from? In terms of the stone industry, the people living there were equivalent to the Neanderthals. Their industry was also a version of the Mousterian tradition. Anatomically, they were different from the Mousterians, not having the cold weather adaptations. It seems likely that these people were some kind of Homo heidelbergensis, which first appeared in Africa about 600,000 years ago. For much of the time after Homo sapiens evolved in Africa, they shared the land with more primitive ancestral populations.

Outside Africa, the earliest definitely-modern human remains have been found at Jebel Qafzeh in Israel,

Around 100,000 years ago, a new industry appeared near the Atlas Mountains in the northern Sahara. This is a more complex version of Mousterian type technology, and is associated with modern humans. This Aterian industry has a key feature in the development of tangs or stems - that is, projections on stone tools. These projections clearly indicate that such tools were hafted, tied to wooden or bone handles. Aterian technology is derived from Mousterian technology, and uses pretty much the same techniques. However, the tools produced are differently fashioned, and of good workmanship.

Tangs on spear points show that they were used as spear tips. Aterian sites are widespread across the Sahara, reaching Egypt in the east from Tunisia in the west. This was probably the most widely distributed tool industry in the Sahara. During this period, the Sahara was a green savannah grassland, filled with a variety of wildlife, including antelopes and gazelle, ostriches, warthog, large bovids, the white rhinoceros, and species of camels, as well as a large number of birds. Aterian people were spread out in numerous settlements across the area that is today the Sahara desert.

The smaller aterian points almost certainly were used for thrown weapons. There is no evidence of bow manufacture, and the points are somewhat large to be used as arrow heads, The usual interpretation is that they were used on thrown spears, possibly aided by some sort of mechanism such as an atalatl.

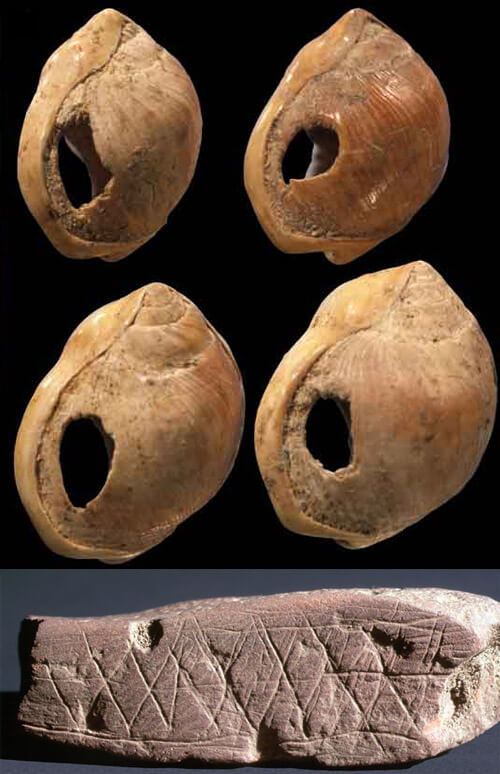

Items of personal adornment, such as pierced beads are also found at many Aterian sites, some dating to as much as 82,000 years old. Even older shells pierced to make beads have been found at sites in Israel and Algeria, which possibly date to 90,000 - 130,000 years old. These, together with similar goods from Blombos Cave in South Africa, are some of the oldest known non-utilitarian items known to have been produced by man. Such items are important in establishing when modern human behavior first emerged. Humans show a highly conceptual understanding and abstract mode of thinking, which is not as developed among other animals. Since the evidence of modern expressions of such thinking, such as language or writing or art is absent from the early record, anthropologists use other proxies for the emergence of symbolic thought. Articles of personal adornment such as beads, or artistic value such as stone carvings, can be used as evidence of symbolic thought. The next section deals with this in more detail.

The Aterian culture ended about 30,000 years ago, with climate change and the drying of the Sahara, which made the region inhospitable.

Origin of Modern Behavior

Although modern humans first appeared about 200,000 years ago, one interesting question is when did modern human behavior first emerge? By "modern human behavior", we mean evidence of culture and symbolic thought. Today, humans do certain things that no other animals do. We communicate using a complex language. We build things. We have art. While it's true that certain animals show rudimentary capabilities in these directions, humans do these things on a much higher level of complexity. What are the earliest available signs of such behavior?

For many decades, the accepted view was that modern human behavior emerged about 45,000 years ago, in the Aurignacian culture of Europe. From this point on, many artifacts are found which indicate symbolic thought, such as ornaments, small figurines, bone whistles or flutes, and later, cave paintings. There are perhaps good reason for this. At present, we have no evidence of any significant changes in human physiology across the time span of our species. There is no difference that we can detect between a modern human skeleton that is 100,000 years old, and one that is 10 years old, which might explain why we build cities and they didn't.

Of course, it's always possible that there were subtle changes in the brain that don't show up in fossils of the skull. However, there is no positive evidence of such changes either. It seems reasonable, therefore, to think that perhaps it was not a change in our physiology that led to the "cultural revolution", but a change in something else.

One candidate is language. A complex, grammatical language is necessary for the communication of new ideas that are being discovered, new techniques that are being invented. Many other animals, such as chimpanzees can be taught new techniques to acquire food, for example, and then they will teach these techniques to other chimpanzees. But such teaching remains mostly visual - teaching by example - doing the trick over and over until the viewer "gets" it. Language, on the other hand, makes possible the communication and teaching of much more complex ideas, some of which are not easily taught visually. It also makes for much more rapid dissemination.

Unfortunately, we do not know when language emerged. Of course, like other great apes, our ancestor species probably communicated through grunts and signs, and may have had a substantial vocabulary of such symbols (by "symbol" I mean something, a sound, a sign, body language, etc. that conveys some specific meaning to the audience). We do not know whether they had grammar, but we know that chimps are quite smart, and our distant ancestors must have been even smarter. After all, human ancestors were routinely using fire over 700,000 years ago, and there is evidence of them building crude habitations, over 400,000 years ago. And, of course, they were flaking stone to make crude tools 2.5 million years ago. These things are arguably more complex than chimpanzee behavior today, so it's not a stretch to think that our distant ancestors were more complex than chimpanzees in the matter of communication. By the time our own species appeared 200,000 years ago, language may have been quite evolved. However, we have currently no way to prove this.

One proxy for language that is often used is the appearance of symbolic objects. While tools have been manufactured with ever increasing sophistication for 2.5 million years, purely decorative objects are much newer in the archeological record. Many anthropologists think that a concern with self, as in self-adornment, or the creation of purely esthetic objects, indicates symbolic thought - a sign of a species that thinks in abstract terms such as form and beauty. They argue that such thinking must be accompanied by language. This does not seem a very controversial idea, since language was very likely evolving throughout our mental development, from the crude tools of 2.5 million years ago to the much more polished tools and refined techniques of more recent times. Language should have both permitted and adapted to the development of new kinds of symbols to represent more abstract ideas.

So the appearance of symbolic objects in the archeological record is considered good evidence of behavioral complexity and modernity. When do such items first appear? As mentioned earlier, they appear in great profusion after about 45,000 years ago, in Europe. However, more recently, we have started finding them even earlier in Africa and Asia. Some date to as much as 100,000 years old. There are even older claims, going back to 200,000 years in the case of ostrich eggshell beads from Wadi el Adjal in Libya. Robert Bednarik has a couple of very interesting articles that discuss such ancient symbolism in great detail, that are well worth reading:

- Beads and the origins of symbolism, and

- A global perspective of Indian paleoart.

Pushing back modern behavior this far raises the question - why not push it all the way back to the dawn of our species? After all, we are still making discoveries, and older finds are naturally rarer than more modern finds anyway, because the added age increases the chances of degradation. So if we have found nearly 100,000 year old artifacts, what's to say even older ones don't exist? They might, and if they do, perhaps modern behavior is just a feature of our species. In this case, we are left to explain the somewhat patchy record of such finds. Typically, we find artifacts at a site dating to a certain period. Then we find no such artifacts for a period of say 10,000 years (meaning, we continue to find tools from these intervening periods, but no "symbolic" artifacts), and then they reappear again, somewhere else. The entire record of such "symbolic" artifacts is patchy in the 100,000 - 45,000 year old period. After about 45,000 years ago, it becomes regular and sustained.

Obviously, if our ancestors were capable of making such objects 100,000 years ago, then they were behaviorally modern at the time. Why then do such objects disappear from the record for long periods of time? One answer is population density. For a large part of our history, humans populations have been very sparse. There may have been no more than perhaps 100,000 humans, distributed over the entire continent of Africa. With people living in small family bands, it's quite possible that humans saw no one outside their band for years, perhaps for generations. New skills and ideas may have been acquired independently by multiple people, multiple times. But due to death and attrition, such discoveries died with them, or soon after. It's only when population density reaches a certain critical point that new developments begin to "take hold" - spreading fast enough and far enough to ensure their survival past the vicissitudes of life in ancient times.

Computer modeling studies support this idea. Additional support comes from DNA studies, which indicate that many sites where symbolic artifacts are found date from periods when there was a population expansion. Human populations underwent several such expansions and contractions (even bottlenecks) regularly, until about 45,000 years ago.

It is also important to remember that such symbolic thought may not be unique to our species. There are several Neanderthal sites where evidence of pigments used as paints has been found, including equipment which shows that the materials were deliberately brought to the site, prepared as paints, and even instruments used for the mixing and application of paints. However, most of these sites are relatively recent, after modern man also appeared in Europe. So the thinking has been that Neanderthals may have used body decoration and paints, but they learned it from modern Homo sapiens sapiens. This view is starting to change with the discovery of a Neanderthal site in Murcia, Spain, which is dated to 50,000 years old. Pigments, possibly used for cosmetic purposes have been found at this site, and this dates to about 10,000 years before modern humans appeared in this part of the world. So it's not possible to attribute this development to the Neanderthals acquiring the knowledge from modern man. Perhaps even older Neanderthal sites will turn up similar evidence of symbolic thought, but so far the oldest such sites all belong to modern man. The complexity of such symbolic objects is also greater at sites associated with modern humans.

Here are a couple of the older (middle paleolithic) sites from Africa that are particularly interesting.

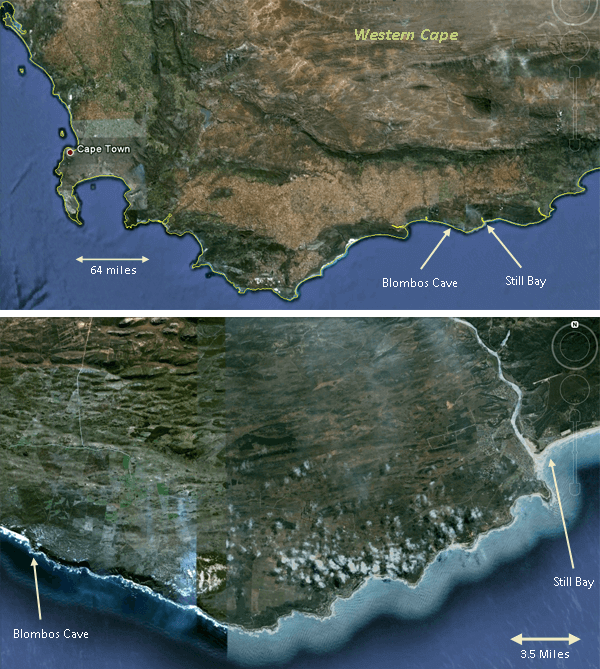

Blombos Cave

Blombos Cave is part of the Still Bay - Howiesons Poort complex at the southern coast of South Africa, about 160 miles east of Cape Town. These areas have archeological sites from the middle paleolithic, dating from 77,000 - 70,000 years old for Blombos Cave and Still Bay, and about 66,000 - 58,000 years old for Howiesons Poort. The remarkable feature of these sites is that they show evidence of modern behavior that is at least 20,000 - 30,000 years older than found elsewhere in the world.

Blombos Cave is located in a limestone cliff, about 35 meters above sea level, 100 meters from the coast. During the period of occupation, the distance of the cave from the coast has varied due to changing sea levels. It shows evidence of human occupation as early as 140,000 years ago. There are 3 different phases of human occupation during the middle stone age, the earliest from 140,000 - 100,000 years ago, the next at about 80,000 years ago, and the most recent about 73,000 years ago. There are also more recent layers, showing human occupation during the upper paleolithic. Occupation was relatively short during each phase, with layers no more than 10 cm thick. The cave was apparently occupied for short periods, with long intervals of non-occupation in between. This probably had to do with the distance from the cave to the coast, since the sea and coast were important as food sources to the inhabitants. During the periods of occupation, the distance of the cave from the coast varied between about 100 meters and 1 km. During the last glacial maximum about 17,000 years ago (when the cave was unoccupied), it was around 160 km from the coast.

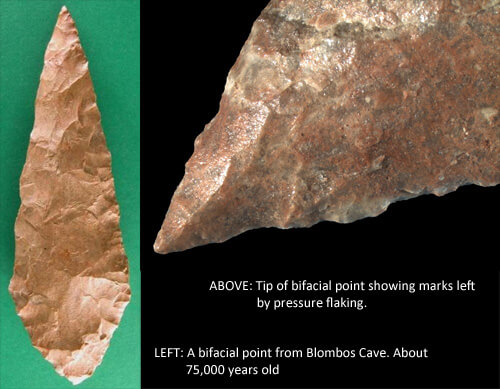

The earliest occupation is represented by bifacial foliate points, typical of the local stone industry, which resembled Mousterian industry. Over 400 such points have been recovered from the cave. There are also lots of flakes, indicating that the points were created at Blombos, rather than transported in from elsewhere.

Over 60 "beads" were found from the 73,000 year old level. These beads are actually gastropod shells (Blombos is the earliest site showing evidence of extensive shellfish use in the diet, and possibly also the earliest evidence of fishing), which have been deliberately pierced with holes, using bone tools. The beads show signs of wear where they rubbed against each other, showing that they were strung into chains. About 27 of the 60 beads appear to come from the same string. There are ochre traces inside the beads, possibly because they were painted with ochre, or because of rubbing against the body of the wearer, who was painted with ochre. These are among the earliest evidence of personal adornment by humans.

Over 1000 fish bones were found at the site, including some from large aquatic mammals such as seals and dolphins. This seems to imply that humans at this time were cooperative hunters, and at least at this location, depended significantly on the sea for food.

No human remains have been found other than 9 human teeth. It's hard to tell much from the teeth other than they probably came from fairly gracile humans.

Several fragments of ochre stones (ochre is a reddish stone rich in iron ore, that was much used for painting in the old days) decorated with geometric lines were also discovered. The nearest source for ochre is at least 20 miles away, indicating that it was deliberately brought to the cave. The geometric lines seem to suggest the capacity for symbolic thought, and probably a language. These issues are hotly debated. Random fiddling with objects (which many other animals do) does not produce geometric patterns. They seem to indicate some degree of abstract thought in their creation, but we will need to await more such finds before jumping to conclusions.

This region of South Africa is also known for preserving the oldest known footprints of an anatomically modern human, probably a female or otherwise small person. The footprints are about 117,000 years old, showing that modern man had spread to the southern tip of Africa by that time.

Middle stone age technology does not show any "progression" except in a broad sense. There are variants. Various techniques appear and disappear at different times. Bone awls, bead work, gluing technology, all appear to come and go in different sites at different periods. This makes it hard to argue for some sort of gradual evolution of the human brain which produced more and more complex technologies. It seems more likely that such technologies were contingent on particular environments and situations, and that the ability to produce them was largely present across the population. This is very different from the "cultural explosion" seen in the upper paleolithic, but it is interesting that the antecedents of that cultural explosion (bead work and carved lines perhaps foreshadowing the splendid cave art of the upper paleolithic) were present in the middle stone age, at least from about 90,000 years ago and onwards. Significantly, these advances coincide with a period in which there was a rapid expansion of the human population, which also led to the first human migrations out of Africa.

There are other sites within a short distance of Blombos Cave that also show such "symbolic" artifacts. These date to roughly 65,000 - 60,000 years old. The appearance, therefore, is that such modern behavior appeared at Blombos between 73,000 - 70,000 years ago, died out, then reappeared nearby about 65,000 years ago, to last another 5,000 years in this part of the world. This sort of cyclic appearance and disappearance is characteristic of pre-45,000 year old cultural revolution, and may have to do with population density and the transmission of such ideas and technology.

Update

In the October 29, 2010 issue of Science, Mourre, Villa and Henshilwood reported that the bifacial points found at Blombos Cave and Still Bay were probably shaped by pressure flaking, at least on their tips. Pressure flaking is a technique for lithic reduction in which a sharp tool is used to apply firm pressure on the object being shaped, as opposed to percussion - striking it with another stone. The stone being shaped is grasped in one hand, while the other hand is used for manipulating the flaking instrument. This is a complicated technique and requires a great deal of manual dexterity and experience. The biggest problem is that the sharp edged tools (which are themselves made of stone or bone or antler) break during the flaking process, usually from fractures due to a torque being applied. Care needs to be taken to apply the pressure evenly, and not twist the tool. Pressure flaking allows for creating much sharper points, and also other fine shaping such as the addition of notches, which can be used to bind the point to a stick to use as a spear.

Previously, the earliest evidence of pressure flaking was from Solutrean tools from Spain, dated about 20,000 years old at most. Therefore, the evidence from Blombos Cave and Still Bay push back the use of this technique by at least 50,000 years, which is remarkable indeed.

The Blombos Cave spear points are made of silcrete, which is quartz grains cemented by silica. Unlike some stone material (such as obsidian, jasper or some high quality flint), silcrete is not easily pressure flaked unless it is heated first. A year ago, Brown et al reported in the August 14, 2009 issue of Science that they had found the earliest evidence of the heat treatment of stone in order to make high quality tools at Pinnacle Point, one of the Still Bay sites. Heat treatment, probably by burying the stone beneath a campfire and leaving it there for a day or two, was being done at Pinnacle Point at least 72,000 years ago, and possibly as far back as 164,000 years ago. There are various techniques for detecting heat treatment, such as archeomagnetic study (heating realigns magnetized grains in the object, thus changing its polarity), thermoluminescence, and changes in the maximum glossiness of the object (which is affected by heating).

These bifacial points from Blombos Cave provide the first evidence that heat treatment was used to temper stone to make it suitable for pressure flaking, and was subsequently in fact pressure flaked to create very sharp points. The use of such relatively modern techniques 75,000 - 72,000 years ago in South Africa should make us reassess the emergence of behavioral modernity in humans. Increasingly, the signs are that there is little difference between anatomical and behavioral modernity, that Homo sapiens has had the capability for behavioral modernity probably since their emergence 200,000 years ago, and that the sporadic appearance of modernity in the archeological record represents periods during which population levels were sufficiently high in a certain location to produce and sustain modern behaviors for long stretches of time. No doubt we will find such evidence to be much more widespread as more discoveries are made.

Python Cave, Tsodilo Hills

This is a site in Botswana in South Africa, where in 2006, Sheila Coulson of the University of Oslo made the discovery of a cave that was inhabited 70,000 years ago by modern man. The San people (bushmen) live there today.

The archeologists found a large rock (about 6 meters by 2 meters) that was naturally shaped like the head of a python. This rock had about 300-400 markings on it, to represent eyes and scaled snake skin. These markings were obviously man made, and looked very old. It is not possible to date the markings, but they were extensively eroded, signifying that they were not recent.

Inside the cave, they found a large number of spearheads, as well as stones used to carve the spearheads. In all, they found about 13,000 objects. Some of these could be dated from the strata in which they were found, and the dating indicated that they were about 70,000 years old, around the same time as Blombos Cave, which is not very far to the south.

These spearheads are unlike other spearheads from the same time/area, in that they are more carefully carved. The stone used to make them is not local, but was brought in from some distance (the closest known source of the material is in Namibia). Further, some of the spearheads appear to have been deliberately destroyed. Some were destroyed by breaking them in half, while others were destroyed by burning. Interestingly, the only type of spearheads that appear to be destroyed by burning are the ones made from reddish stone.

No other human artifacts, no other signs of habitation have been found in the cave. There are no remains of hearths, no animal bones to indicate that people ate meals here, or lived here for extended periods.

Because of these peculiarities, the archeologists who discovered the cave posit that the cave had ritual significance, that the rock decorated into the form of a snake, the carefully crafted spearheads, the deliberate destruction of the red spearheads, the absence of any signs of the normal activities of habitation, such as cooking and eating - indicate to them that the cave was used for special purposes only, and that these purposes appear ritualistic.

Interestingly, the python is still revered among the San people living in the area today. There are two small cave paintings inside the cave - an elephant and a giraffe, which are both sacred animals to the San. These paintings are probably much more recent (this whole area is one of the richest areas of the world in terms of rock paintings, which are mostly about 1,500 years old or somewhat older). The cave and the hill in which it is located are considered sacred by the local San people.

If this cave was indeed used for ritual purposes, it indicates modern behavior at 70,000 years ago in this region. It would be specially important because of the type of modern behavior - ritualistic - since we have evidence of other sorts (adornment, geometrical carvings, etc.) from other sites as well, expanding the range of the modern behavior.

Not all archeologists agree with this interpretation. Rocks brought in from a distance to refine into tools are not uncommon for this period. Deliberate destruction by snapping them into half is harder to explain, but it's difficult to draw conclusions, without more information, such as were these tools at the end of their useful life? Destruction by fire could be accidental; perhaps fire was used for hardening the tools and some got destroyed in the process. The carvings on the python-shaped rock seem deliberate, but cannot be dated directly. They may have been done later. This possibility is supported by the fact that although they are positioned on the rock so they enhance the rock's python-esque appearance today, the the middle stone age the ground was several feet lower, and some of the markings would probably not even have been visible from ground level. Further research may settle these points.

You may wish to read a general introduction to the paleolithic, read about the lower paleolithic, or move on to the next article in this series on the upper paleolithic.

At EssayWeb.net, we can craft a chapter or the entire research paper or dissertation. Likewise, we can efficiently deal with smaller writing assignments like essays, reports, reviews, etc. Highest quality, 100% originality, affordable prices, fast delivery guaranteed!

Cite the page

- APA

- MLA

- Harvard

- Vancouver

- Chicago

- ASA

- IEEE

- AMA

If you want a unique paper, you can have one of our writers create it for you

Ours Services

Related Essays

Academic Essays Database Has All You Need to Succeed

- Essay

- Research Paper

- Case Study

- Report

- Critical Thinking

- Article Review

- Argumentative Essay

- Term Paper

- Literature Review

- Business Plan

- Research Proposal

- Creative Writing

- Cover Letter

- Dissertation Conclusion

- Dissertation Methodology

- Dissertation Proposal

- Dissertation Abstract

- Dissertation Hypothesis

- Dissertation Chapter

- Dissertation Results

- Dissertation Introduction

- Thesis

- Thesis Statement

- Business Proposal

- Biography

- Annotated Bibliography

- Admission Essay

- Movie Review

- Thesis Proposal

- Personal Statement

- Coursework

- Book Review